| Uma comédia no estilo realismo mágico que fala de perda, amor, mudança e redenção. Lane é uma médica muito séria e focada em sua carreira, que contrata uma empregada doméstica bastante peculiar. O poblema é que Matilde, a empregada, odeia limpar. Ela sonha mesmo é em ser uma comediante e pensar na piada perfeita, aquela que faria com que o ouvinte morresse, literalmente, de tanto rir. Lane é deixada por seu marido, que está apaixonado por uma mulher latina mais velha em quem acabou de fazer uma mastectomia. Só que a doença persiste e envolve a vida de todas as personagens. THE CLEAN HOUSE foi finalista para o Pulitzer Prize de Drama de 2005. Sarah Ruhl recebeu o MacArthur Fellowship "Genius Grant" em 2006. |

| Dramaturgia | Sarah Ruhl |

| Direção | Rebecca Taichmann |

| Assistência de Direção | Estefania Fadul |

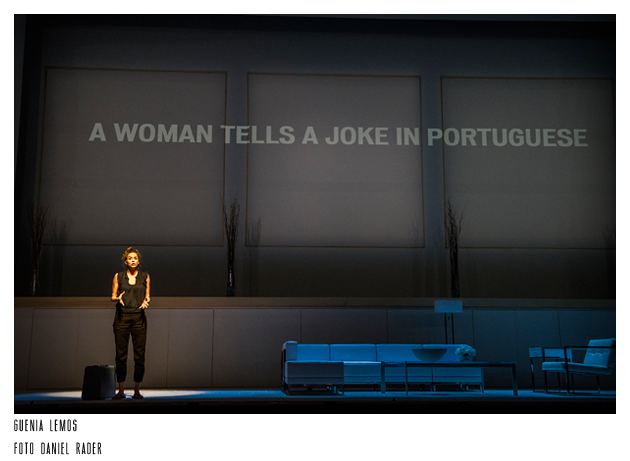

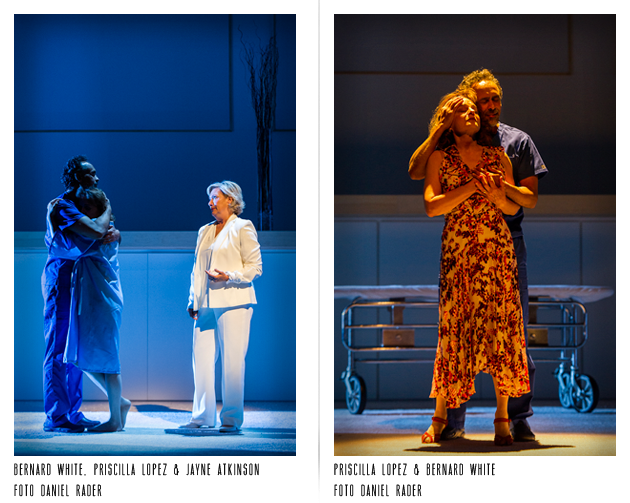

| Elenco | Guenia Lemos, Jayne Atkinson, Jessica Hecht, Priscilla Lopez & |

| Bernard White | |

| Understudy | Franca Sofia Barchiesi |

| Direção de Produção | Lloyd Davis, Jr. |

| Assintência de Produção | Logan Pratt & Kailie White |

| Direção de Movimento | David Neumann |

| Iluminação | Ben Stanton |

| Figurino | Anita Yavich |

| Cenário | Riccardo Hernandez |

| Sonoplastia | Andre Pluess |

| Direção de Dialeto | Ben Furey |

| Casting | Telsey + Company |

| Direção de Produção | Eric Nottke |

| Gerente de Produção | Brandon Kahn |

| Comunicação e Marketing | Josh Martinez-Nelson |

| Direção Artística do Festival | Mandy Greenfield |

| Realização | Williamstown Theatre Festival |

| THE CLEAN HOUSE estreou no Theatre do Wiliamstown Theatre Festival, Williamstown, em 2017. | |

| THE BERHSIRE EDGE |

| "The Clean House" at WTF - stellar cast in a dark comedy |

| J. Peter Bergman |

“This is NOT a foreign film!” When the Yiddish word “bashert“ is introduced into this play by Sarah Ruhl, “The Clean House,” in the second act, everything changes. Everyone changes as well. It comes not as a surprise but as a shock. It turns an awkward, nearly ugly moment into something quite different and the play, a strangely sprightly comedy with a dark side, into a drama of romantic torment, enlightenment and magic. Amazing what a single word can do, a single commentary, a single concept. Sarah Ruhl wrote one of my favorite plays, which may prove to be too difficult to do in summer theaters: “In the Next Room: The Vibrator Play.” Its use of magical realism was spectacular and, I thought, unsurpassable. In this production of another of her plays at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, magical realism rears its magnificent head and leaves the audience stunned by its beauty, fascinated by its impact. Although I’d already selected my favorite play of the year, Ruhl’s play in its Rebecca Taichman production is shoving aside other considerations –and it’s only mid-season. Taichman’s production of the play “Indecent” on Broadway this past season proved to be my favorite show in New York and its Tony Award was so well deserved. Add to the fabulous mix of playwright and director a stellar cast consisting of Jayne Atkinson, Jessica Hecht, Guenia Lemos, Priscilla Lopez and Bernard White, and throw in the technical beauty of Riccardo Hernandez’s set, Ben Stanton’s lighting, Andre Pluess’ sound and costumes by Anita Yavich, and the end result is a play that is definitely not to be missed. For the 1950s musical “The King and I,” Oscar Hammerstein II wrote a lyric that sings “you fly down the street/on the chance that you’ll meet/and you meet, not really by chance.” So it is for the people in this play. Virginia (Hecht) meets Matilde (Lemos) and magic happens, as it must when yin and yang collide over the concept of housecleaning. Charles (White) and Ana (Lopez) meet over breast cancer and suddenly little else matters but Ana and Charles. Lane (Atkinson) meets no one, for she is interested in no one but Lane and, even so, the miracle of new relationship occurs for her. Magical realism concerns itself with transformational concepts and, in this play, they happen all the time – sometimes in a grand and beautiful manner, sometimes in a small shift of attitude. Don’t be misled by all this grandiose thought. This is a play about love, loyalty, the prescience of humor and the value of a good joke. It is about laughter and about tears, about hopes and about fears, about accumulated dreams over accumulated years. It deals equally with life and with death and the ramifications of both. It is as though some unseen Tinker Bell has sifted a bag of fairy dust over us all and transformed subtly our ability to soar. Newcomer Guenia Lemos plays Matilde, a Brazilian child of loving jokesters brought together and killed by laughter. An actress of power and beauty, she regales us with jokes in Brazilian Portuguese and makes us laugh without knowing a word of the language. She plays a woman with goals who cannot express them but who makes them obvious to everyone. Matilde (pronounced Ma-chool-gee) is the distributor of loving fairy dust who should clean it up but is reluctant to do so. Her need for affection and a good listener inspires Hecht’s Virginia and the relationship they build is absolutely honest and ever so touching. Hecht could be the star of this production but her role is a secondary one, no matter how much we come to love her, almost from the outset. This actress has the ability to change the mood and motion of a sentence mid-word without allowing that change to feel acted or artificial. She is a natural for this role – Virginia – the discontented malcontent content with her life, or so she says. She has a wonderful way of moving, converting a natural grace into an equally natural awkwardness. Of the four women, she is the most compelling most of the time and it is her ability to make the role seem real and happening that gives the play its ground floor, its base. Priscilla Lopez is the intruder, Ana, whose understanding of “bashert“ creates the changes in the play. The word technically, rabbinically, means “from God or the consequence of divine intervention” though, in this play, it is described as “soulmate.” Ana, a beautiful older woman, brings this quality into the life of doctor Charles, who is married to Lane. He has no desire for another woman, but Ana alters his perception of life almost instantly and he does the same for her. Lopez is lovely in this role, bringing a bizarre simplicity into the most radical of ideas. She does this with physical grace and amazing poise. She is as delightful a companion for us, the audience, as she is for Charles. Bernard White is a romantic Charles. As he falls under Ana’s spell, he exudes his own, casting her into a net from which she cannot escape. Physically he manages to wrap all the women into a spell he has no idea he can cast. Watching this actor work through this process is like standing outside an old-fashioned pizza parlor watching the baker through the window as he expands his dough with lusty thrusts of two fists into the descending disc of dough. You are fascinated, mesmerized by his technique and his talent. It is as though there is nothing else to see. Changes come slowly, almost furtively, to Lane and she battles with each of them in turn. This is a woman easily thwarted but never seduced or reduced in any way from the perfect champion of a woman that she is. Jayne Atkinson makes the most benign collection of words in a sentence into something outrageously funny or equally oddly moving. She starts out stiff and officious but, by the end of the play, she has softened enough to accept the realities of her life without grimace, tears or scotch on the rocks. Atkinson leaves herself out of the mix here, playing a role that is everything she has ever done and something she has never become before. Her version of Lane is simply this: a woman who cannot undo herself even when she tries to do so, and who cannot remain herself even as she attempts to do just that. The main character in any good play needs to make a transition, to move from point A to point B somehow. Though her Lane seems incapable of achieving this, it is the play’s magical realism that takes Atkinson by the hand and guides her through Lane’s reticence. I loved watching the gradations of change, small and sometimes temporary. I loved hearing her dark tones as she accepted herself for who she is. Lane is truly alive in Atkinson’s performance, nuanced and subtle and strong. The magical realism of Ruhl’s fine play is almost a warning to the audience: We are alerted to the possibilities of what the world holds in store for us. Atkinson is the toughest symbol of this concept and Hecht is the easiest. Matilde’s need for the perfect joke is the posted landmark for the journey these people make in the quest for the most real things in their worlds. They take a journey that is so very worth the making. I’d make it again with these folks. Any day. |

| THE BERSHIRE EAGLE |

| Laughing matters in "The Clean House" at Williamstown Theatre Festival |

| Jeffrey Borak |

WILLIAMSTOWN — Two women in Sarah Ruhl's "The Clean House" — which is being given an extraordinarily accomplished, richly funny and incisive production at Williamstown Theatre Festival — die laughing, literally; one of them long before the play's action has begun; the other in full view on stage in a gracefully orchestrated scene at the end. But Ruhl's daring, magnificently balanced play has as much to do with how we choose to live our life as how we choose to end it. |

| BROADWAY WORLD |

| Sarah Ruhl'' "The Clean House" at Williamstown Theatre Festival |

| Justin Sacramone |

Meet Lane, an accomplished, confident, pant-suit wearing woman of medicine who values (no wait, demands) cleanliness. Lane lives in a beautifully crisp "metaphysical" Connecticut home and has no time for the mundane tasks of homemaking. Meet Matilde, an out of work comedienne from Brazil who recently lost both parents due to extraordinary circumstances and goes to work for Lane as a housekeeper only to discover cleaning clouds her creative process and makes her depressed. Meet Virginia, Lane's sister, who values cleaning as a holistic approach to self-awareness. Virginia offers up her services to Matilde with the dual goal of reducing Matilde's depression while doing her sisterly duty of checking in with Lane's mental state. Now revived at the Williamstown Theatre Festival under the direction of Tony winner Rebecca Taichman, THE CLEAN HOUSE earned playwright Sarah Ruhl her first recognition as a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2005. Ruhl's lyrical comedy has been produced at some of the nation's top regional theatres leading THE CLEAN HOUSE to tie as the second most produced play in the 2007-2008 American theatre season. How exactly does a play about housekeeping go on to receive such accolades? Ruhl's ability to craft her plays with almost no exposition or outside world substance and still be able to make her characters act and sound human while experiencing larger-than-life tribulations is perhaps what sets her ahead of other playwrights. THE CLEAN HOUSE successfully demonstrates how a play can be entertaining during the performance and then resonate on a deeper level afterward. The visual image of Virginia performing the white glove test on Lane's living room lamp is hilarious, yet, once the laughs from the audience cease, we are left wondering what all the accumulating particles symbolize. The challenge in mounting any Sarah Ruhl play is unearthing and then maintaining the bizarre wavelength on which her characters operate. In THE CLEAN HOUSE, laws of physics break, speaking patterns are odd, the narrative takes sudden and baffling turns, and Ruhl never attempts to spoon feed explanations. I've seen productions of Ruhl's work collapse when a director treats the material as an absurdist tale, or with a straight up serving of realism. True, both of those elements have a place in her plays, but the exciting part is seeing the erratic departure from realism into something less compact. Acknowledging that challenge gives a deeper appreciation for Williamstown Theatre Festival's decision to place acclaimed director Rebecca Taichman in charge of wrestling THE CLEAN HOUSE into a production making sense of all fringe elements Taichman is a frequent collaborator on Ruhl's work (from my count she has directed six Ruhl plays including a 2006 production of THE CLEAN HOUSE in D.C.), so her intimate relationship with the playwright's dramatic style and text combined with her exquisite visual eye make for a successful formula. Taichman crafts each moment beat-by-beat with searing clarity and defined emotional logic that presents even the most dramatic moments truthfully. Taichman proves, yet again, she's a master at combining grand theatrical aesthetics tickling the surreal side of Ruhl's work with natural performances of an acting ensemble. Jayne Atkinson (Lane), Jessica Hecht (Virginia), Guenia Lemos (Matilde), Priscilla Lopez (Ana), and Bernard White (Charles) make up the cast of five and operate in harmony throughout. It's our two sisters who end up walking away with the show. Atkinson and Hecht, both accomplished stage actresses, deliver characters full of wisdom, quirks and droll comedic timing. Atkinson is great at contradicting Lane's confidence as an accomplished doctor with the insecurity surrounding her household duties. The way Atkinson portrays Lane's avoidance borders on fear and allows for an easier digestion of Ruhl's "cleaning house" metaphor. Lane's sister, Virginia is the play's biggest mystery. While the internal conflicts of the other characters are more visible to the audience, it's Virginia who goes unexplained and unresolved by the play's end and Jessica Hecht is determined to keep it that way. I often found myself transfixed on her performance even when attention is meant to focus on someone else. So much was going on behind her eyes, I hoped Hecht would let one of Virginia's secrets slip out. Alas, Hecht held onto all of them with the same fierce clutch in which Virginia clings to her handbag. I won't soon forget the sheer delight Virginia takes in standing perched on a step stool with a telescoping duster to clean the last blemish on the otherwise pristine walls of Lane's living room. The play's opening and closing moments addressing the philosophical question of translation is the best expression of THE CLEAN HOUSE's profound message. Through Lane's heuristic journey of connecting her well-defined practical self with her unknown spiritual side, Sarah Ruhl reminds us we have two choices for charting out our journeys. We can waste a lifetime living in a vacuum trying to decipher the mysteries thrown at us or, we can open ourselves up to the voices we've often ignored and do the very thing terrifying Lane (and probably us all): listen. |

| BOSTON GLOBE |

| In Ruhl's masterful "Clean House," an empathy for untidy humans |

| Tery Byrne |

WILLIAMSTOWN — Sarah Ruhl’s “The Clean House” delights in sharp contrasts: the mournful, black outfits worn by a young woman who describes herself as the funniest person on the planet; the doctor whose orderly appearance in white clothing masks the dark mess that lies just beneath the surface of her life. In fact, much of the power of this extraordinary play emerges from Ruhl’s ability to wring so much from these extremes, taking the audience from the heights of laughter to the depths of tears. The beauty of the current Williamstown Theatre Festival production lies in director Rebecca Taichman’s ability to embrace Ruhl’s imaginative universe, while steering her cast toward the characters’ subtler moments of unexpected connection. Those moments, which often come with an exchange of glances between two characters, a pause, or a simple gesture, add another compelling layer to this moving comic-drama The play opens with a maid named Matilde (Guenia Lemos) telling a joke in Portuguese. Lemos delivers the joke with so much physical exuberance and verbal enthusiasm that even though we have no idea what’s so funny, we are eager to know more. In short order, we learn that cleaning makes Matilde sad and prevents her from her life’s work: thinking up the perfect joke. Coming up with jokes is her birthright, since her parents were the funniest people and her mother died laughing at the perfect joke her father told. Fortunately, Virginia (Jessica Hecht), whose sister is Matilde’s boss, finds that dust gives her otherwise empty life meaning, and she agrees to clean the house so that Matilde can work on her jokes, without telling her sister Lane (Jayne Atkinson). Just as this tidy arrangement is moving forward, we meet Lane’s husband, Charles (Bernard White), a surgeon, and his patient Ana (Priscilla Lopez), with whom he has fallen deeply in love. The complexities of this set-up might overwhelm another playwright, but Ruhl manages to deftly add increasingly whimsical imagery and ever-deepening emotions without ever losing her balance. Apples tossed from Ana’s balcony land incongruously in Lane’s living room; Charles treks to Alaska to find a tree that might provide a cure for Ana’s cancer; and Matilde has the power to tell a joke so funny that it will make the listener die laughing. All of these flights of fancy are deeply rooted in complex characters whose fragilities and strengths are all on display. Director Taichman has gathered a truly outstanding ensemble to surf these emotional waves with affecting grace. Atkinson, all sweeping gestures and self-confidence, and Hecht, a bundle of tentative, birdlike movements, capture the resentment and tension between two sisters before moving to a deeper understanding of what each can provide for the other. When Lane is so overcome by emotion she alternates between laughter and sobs, Atkinson’s delivery is so sincere, we can’t help but be pulled right along those dramatically opposing emotional directions with her. Lopez and Lemos communicate the passion for life that defies order and reason and demands instead an embrace of whatever surprises life hurls our way. Taichman also gives this production an extraordinary pace and rhythm that encompasses the uneven nature of the way our lives progress. There are choreographed moments, particularly between Charles and Ana, that communicate the sweeping power of love without ever feeling schmaltzy. At other times, the action slows or speeds up, in keeping with the feelings that evolve, from resentment to compassion, allowing the actors to deliver a kind of melody that emerges between the notes. “The Clean House” has a timeless quality that manages to meet us wherever we are and remind us — as Matilde says — that “life isn’t clean, it’s dirty, like a good joke.” |

| THE ARTS FUSE |

| A Superb "Clean House," at The Williamstown Theatre Festival |

| Helen Epstein |

Since the beginning of this century, playwright Sarah Ruhl has been entertaining theatergoers with her absurdist comedies, scripts that are firmly grounded in realities (past and present), though built around strikingly wacky concepts. Ruhl’s Dead Man’s Cell Phone (2007) remains vivid in my mind even though I reviewed it for The Arts Fuse in 2009; in it, a man dies, but his cell phone does not. (At that time 275 million cell phones were being used in the United States.) Ruhl’s genius in that script and in her next play, In the Next Room or The Vibrator Play (2009), was to take an ‘essential’ techno-cultural instrument and make use of it — as a symbol of social transformation as well as a catalyst for quirky dramatic action. In The Clean House, Ruhl starts out by positing the contemporary (personal, professional, philosophical, and cross-cultural) relationship between a woman doctor and her cleaning lady. She then spins a farcical tale that looks at betrayal, the blinders of privilege, the differences between the professional and working class, love, sex, marriage, sibling relations, relations between four very different kinds of women and one man, various perceptions of humor, the lies we tell ourselves to justify what we do, and God knows what else. The play opens in the suburban, all-white living room of a successful doctor couple. (In the program, the location is described as “A metaphysical Connecticut or a house that is not far from the city and not far from the sea.”) The husband is an always-busy, eminent, and charismatic cancer surgeon; his wife, Lane, is not as successful. They employ a Brazilian maid named Matilde who is dressed in mourning and hates cleaning. Matilde quickly figures out that Lane’s husband has fallen in love with a patient when, in the company of the wife’s sister, Virginia, she happens upon a pair of bright red bikini panties in the couple’s laundry. I will not describe the plot twists, hilariously honest monologues, and vividly staged flights of fancy that follow – suffice it to say that they are fabulously theatrical as well as visually and intellectually satisfying. Ruhl started out wanting to be a poet and her dialogue reflects this ambition — her lines can be both lyrical and dramatically effective. “It has been such a hard month,” Lane confesses in her opening monologue, “My cleaning lady got depressed and stopped cleaning my house….I didn’t go to medical school to clean my own house.” Assessing the situation, Virginia takes on the task. The Williamstown Theatre Festival has placed the sparkling wit of Ruhl’s text in the hands of a director, Rebecca Taichman, who is deeply familiar with the impish subtleties of the playwright’s work. Taichman has also chosen an extremely talented cast and a stellar design team. They make full use of the WTF’s massive technical resources; the production’s jokes extend from the verbal to the physical, the visual to the musical. Guenia Lemos is superb as the maid whose name Lane has a lot of trouble pronouncing. The worker may be dressed in black, but she is determined to be funny. The actress takes on the classical servant role, which in most contemporary dramas been relegated to caricature (or silence) and endows it with idiosyncratic vim and vigor. The masterful Jayne Atkinson – clad in elegant white pants and top, a helmet of blond hair on her head, imbues the character of Lane with a Clintonesque competence. She also exudes an obtuse obnoxiousness that seems to channel an Alec Baldwin arrogance when she delivers lines such as “I don’t want an interesting person to clean my house….I want you to do all the things I want you to do without having to tell you what to do.” She is totally convincing as a first-world professional — a little short on empathy for anyone but herself. Jessica Hecht steals her scenes as Virginia, the unappreciated mousy younger sister who is as intelligent as Lane but far more perceptive about other people. For reasons that are left unexplored, she has no job and no children. She likes cleaning because it clears her head. “If you do not clean, how can you measure the progress in your life?” Hecht asks, with flawless comedic timing. The most pleasant surprise in the WTF production for me was to watch Priscilla Lopez. the original Diana Morales in A Chorus Line. She is quite fine as the Argentinian painter Ana, a gracious 67-year-old Other Woman. The WTF set is spectacular. It initially functions as a signboard on which Ruhl’s wry introductions, interpretations, and summaries of the action appear as super-titles in the manner of Jenny Holzer’s text paintings: “VIRGINIA AND LANE EXPERIENCE A PRIMAL MOMENT WHEN THEY ARE SEVEN AND NINE YEARS OLD” says one. “LANE MAKES A HOUSECALL TO HER HUSBAND’S SOUL-MATE” reads another. It would be spoiling the visuals to go into any detail about how the set splits, showing us doings far away from the all-white living room,. Scenic Designer Riccardo Hernandez, Costume Designer Anita Yavich, Lighting Designer Ben Stanton, and Sound Designer Andre Pluess all deserve high praise. Taichman has put together a masterful production of Ruhl’s update of Commedia dell’arte; the evening manages to supply amusement along with the kinds of psychological insight that one expects from serious drama. There is something cleansing about the high spirits of The Clean House in these low and difficult times. |

| BERSHIRE ON STAGE |

| "The Clean House" at Williamstown |

| Roseann Cane |

“The story of my parents is this. It was said that my father was the funniest man in his village. He did not marry until he was sixty-three because he did not want to marry a woman who was not funny. He said he would wait until he met his match in wit. And then one day he met my mother. He used to say: your mother—and he would take a long pause…is funnier than I am. We have never been apart since the day we met, because I always wanted to know the next joke. My mother and father did not look into each other’s eyes. They laughed like hyenas. Even when they made love they laughed like hyenas. My mother was old for a mother. She refused many proposals. It would kill her, she said, to have to spend her days laughing at jokes that were not funny…. I wear black because I am in mourning. My mother died last year.” Playwright Sarah Ruhl places The Clean House in “A metaphysical Connecticut. Or, a house that is not far from the city and not far from the sea.” Matilde (Guenia Lemos), the Brazilian housekeeper who works for physician Lane (Jayne Atkinson), finds herself unable to clean Lane’s home. Lane’s sister, Virginia (Jessica Hecht), enraptured with the sense of order she derives from cleaning, conspires with Matilde to take over cleaning Lane’s house when Lane is at work. And so, for a while, order and cleanliness reign in this house, but Lane’s refusal to inhabit life’s messiness comes at a cost. While she maintains a pristine detachment from her home as well as her feelings, the disorder is filled with revelations. Her laundry contains evidence of a love affair between her surgeon-husband Charles (Bernard White) and his effervescent patient, Ana (Priscilla Lopez), and by the time Lane is confronted with her husband’s new love, she is shaken to her very foundation. A well-lived life, passion, and love are nothing if not messy, Ruhl tells us. This remarkable production, directed by Rebecca Taichman, is rich beyond words, and its sensibility is as filled with surprises as it is with humor and compassion. Ruhl has created a transcendent examination of love in all its forms, brought to life by a smart, sensitive director and a superlative cast. I was gratified to hear during a talk-back after the show that Ruhl was involved with the creation of this production, even going so far as to make some small but stunning changes in the script, which had premiered at Yale Repertory Theatre in 2004, and Off-Broadway in 2006. (Playwrights are notoriously rigid about adjusting their works.) The collaborative spirit between playwright, director, cast, and crew is gloriously evident here. Riccardo Hernandez has created a beautiful split set, with Lane’s crisp white home and Ana’s balcony overlooking the ocean. Anita Yavich’s costumes do a wonderful job of enhancing each character, and the lighting (Ben Stanton) and sound (Andre Pluess) serve the production flawlessly. The Clean House by Sarah Ruhl, directed by Rebecca Taichman, runs July 19-29, 2017 at the Williamstown Theatre Festival on the Main Stage of the ’62 Center for Theatre and Dance. Set design by Riccardo Hernandez; costume design by Anita Yavich; lighting design by Ben Stanton; Sound design by Andre Pluess; movement consultant David Neumann; dialect coach Ben Furey. CAST: Jayne Atkinson as Lane; Guenia Lemos as Matilde; Jessica Hecht as Virginia; Priscilla Lopez as Ana; and Bernard White as Charles. |

| CURTAIN UP |

| "The Clean House" |

| Gloria Miller |

If laughter is indeed the best medicine as the cliche assumes, then a race to Williamstown Theatre Festival for Sarah Ruhl's The Clean House should be the next stop for anyone in need of deep belly laughs and knowing grins, as this fantastical two-act play swirls with the most unlikely set of elements unleashed upon an audience. Yet it works brilliantly as a whimsical study of such diverse topics as the meaning of dust, Portuguese jokes, soul mates, cancer, apple picking, and love-inspired inventions combine to exert a magnetic pull on the fabric of love. |