| Uma comédia no estilo realismo mágico que fala de perda, amor, mudança e redenção. Lane é uma médica muito séria e focada em sua carreira, que contrata uma empregada doméstica bastante peculiar. O poblema é que Matilde, a empregada, odeia limpar. Ela sonha mesmo é em ser uma comediante e pensar na piada perfeita, aquela que faria com que o ouvinte morresse, literalmente, de tanto rir. Lane é deixada por seu marido, que está apaixonado por uma mulher latina mais velha em quem acabou de fazer uma mastectomia. Só que a doença persiste e envolve a vida de todas as personagens. THE CLEAN HOUSE foi finalista para o Pulitzer Prize de Drama de 2005. Sarah Ruhl recebeu o MacArthur Fellowship "Genius Grant" em 2006. |

| Dramaturgia | Sarah Ruhl |

| Direção | Rebecca Bayla Taichmann |

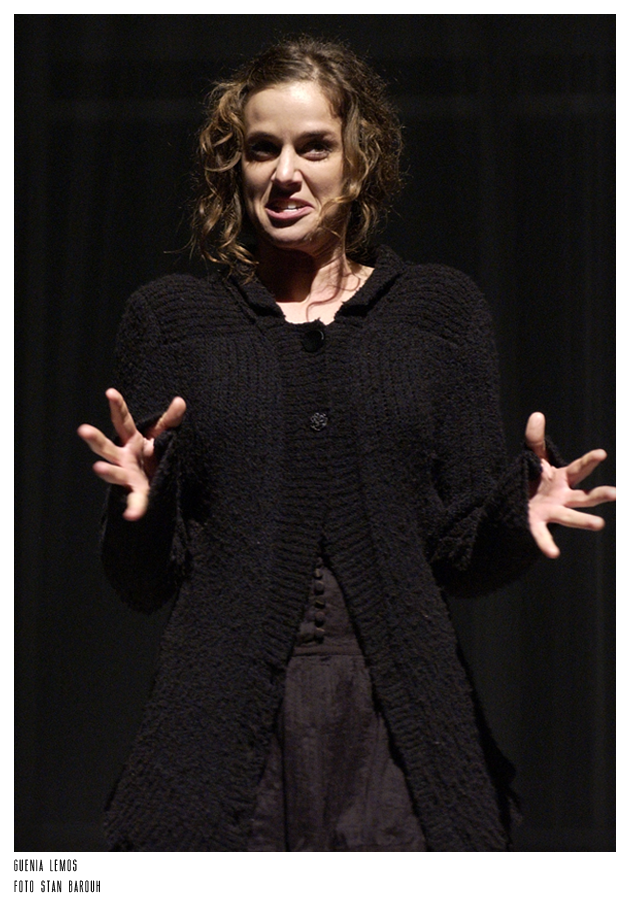

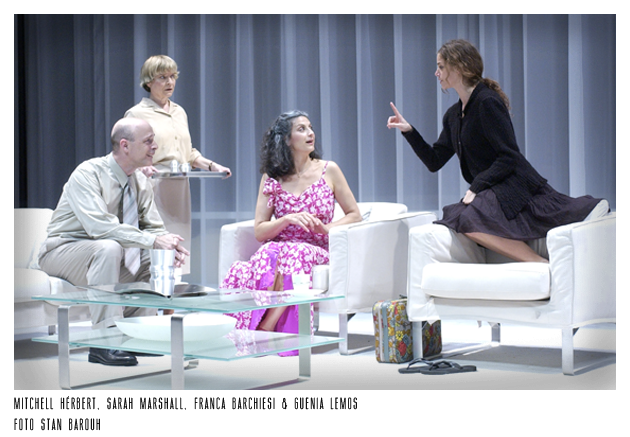

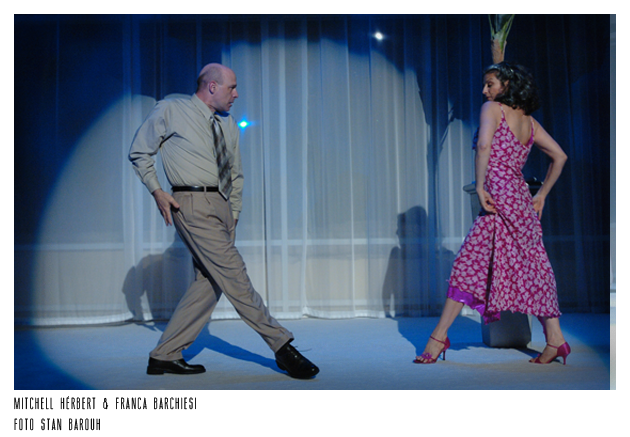

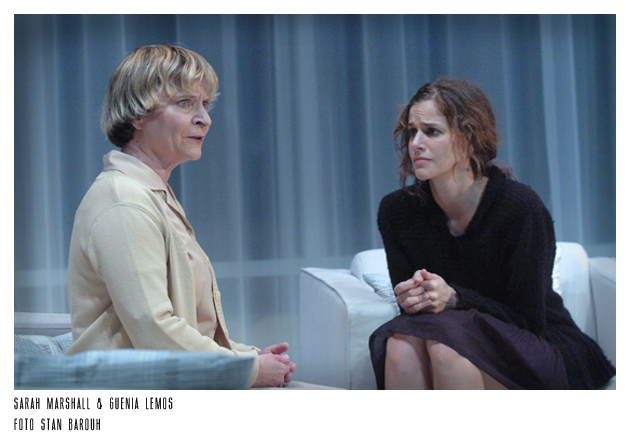

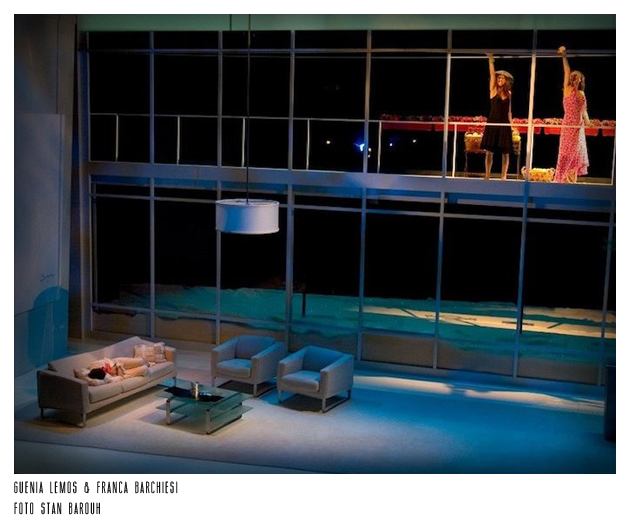

| Elenco | Guenia Lemos, Naomi Jacobson, Sarah Marshall, Mitchell Hérbert & |

| Franca Barchiesi | |

| Direção de Produção | Taryn J. Colberg |

| Assistência de Direção | Patrick Crowley |

| Iluminação | Colin K. Bills |

| Figurino | Anne Kennedy |

| Cenário | Narelle Sissons |

| Adereços | Jennifer Peterson |

| Sonoplastia | Michael Kraskin |

| Muisica Original | Martin Desjardins |

| Letra "Navagação" | Michael Sommers |

| Vocal "Semper Amarus Amor" | Michelle Desjardins |

| Guitarra | Gerard Kunkel |

| Supervisão Musical | Martin Desjardins |

| Fotos | Stan Barouh |

| Dramaturgo | Jacqueline Lawton |

| Diretor Artístico | Howard Shalwitz |

| Diretor Administrativo | Kevin Moore |

| Realização | Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company |

| THE CLEAN HOUSE estreou no Teatro Woolly Mammoth, Washington, D.C., em 2005. | |

| THE WASHINGTON POST |

| "Clean House": A Lemon-Fresh Shine |

| Peter Marks |

"The Clean House" is a delicate play for rough times. The promising young playwright Sarah Ruhl offers up a radical set of notions: that human beings are not inherently selfish, that people can ask for forgiveness and be granted it with grace, that we can live without telling lies to each other -- and even die laughing. Ruhl's style is intriguingly offbeat. Her sense of rhythm and image on a stage puts you in mind of something you might see at Sundance. And the staging her play receives at Woolly Mammoth, under the canny direction of Rebecca Bayla Taichman, accentuates Ruhl's poetic worldview with few harmfully sugary detours. As with most original voices, it takes a while to tune into Ruhl's wavelength. Once connected, though, you commune warmly with her funny and compassionate sense of life's metamorphosing rewards and punishments. The production has been blessed, too, with a beguiling central performance by Guenia Lemos as a Brazilian woman in her mid-twenties who's hired as a maid in a house in what the dramatist calls "metaphysical Connecticut." Not far off, in terms of appeal, is Sarah Marshall, who plays a middle-aged clean-aholic coming apart from too much dust and too little emotional engagement. Franca Barchiesi, Naomi Jacobson and Mitchell Hebert round out a cast that adds a keenly accomplished air to this dramatist's auspicious Washington debut. If the evening begins with each aswirl in his or her own eddy, by the end they've been drawn together in one irresistible vortex. This occurs primarily in the home of Lane (Jacobson) and Charles (Hebert), married doctors too distracted to notice each other anymore. Narelle Sissons's living room is a reflection of the characters' relationship: as sterile as the hospitals in which they have privileges. Everything is white, white, white, which explains the need for the live-in domestic Matilde (Lemos), a dreamy, attractively rumpled young woman whose devotion to housework is about on a par with Paris Hilton's. Fortunately for Matilde, Lane's sister Virginia (Marshall), a depressive for whom an hour with an ironing board is therapy, willingly takes up Matilde's slack and secretly becomes her sister's housekeeper. Marshall gives such an intelligently controlled performance that she manages to make folding undershirts seem a guilty pleasure. "The Clean House," however, is less concerned with sitcom-ish plot formulations than with the mysterious power unleashed by unlikely alliances, such as the bond between Virginia and Matilde, or the one between Charles and the new autumnal love of his life, Ana (Barchiesi). One of the characters is stricken with a terminal illness, but the play's toughest task falls to Jacobson's Lane, a woman with her jaw permanently clenched, who is beseeched by besotted Charles to welcome Ana into their home. Ruhl intermittently has surtitles flashed on a panel above the set, as if her characters were the subjects of a documentary. Some of them are mere recitations of apparent events: "Virginia takes stock of her sister's dust." Others offer ironic commentary: "Virginia and Lane experience a primal moment in which they are 7 and 9 years old." The device is strangely comforting. It adds a spiritual dimension to a play that seems almost as preoccupied with matters of the soul as of the heart. Matilde proves to be a delightfully unorthodox guide through this story of wounds and healing, and Lemos brings an ethereal appeal to her portrayal; her Matilde feels somehow both grounded and guileless. Some of what the playwright asks of her walks right up to the edge of archness. Matilde tells us, for example, that her parents, now dead, were "the funniest people in Brazil" and that she is on a mission in their honor to compose the perfect joke. Oddly enough, this quest serves a purpose at the play's climax, which touchingly justifies the several curious scenes you've sat through, listening cluelessly to jokes in Portuguese. As it shifts from the consolations of housework to those of death and dying, "The Clean House" mixes whimsy and solemnity a bit too artificially. (The journey by Charles to Alaska in search of a yew tree is one plot twist too many; by this point, we've already been apprised that he'd do anything for Ana.) Still, there's a moving idea of reconciliation in the production's final movement that's extremely well handled by Taichman and her ensemble. Up next for Ruhl is another Washington assignment, the premiere at Arena Stage later this summer of her epic-length "Passion Play." It's something to look forward to. For the best reasons, "The Clean House" leaves you wanting more. |

| THE WASHINGTON TIMES |

| Life gets scrubbing in "The Clean House" |

| Jayne Blanchard |

Washington is on a roll -- and we're not talking baseball. In the space of a single week, two astounding new talents have arrived on the theater scene. First, Studio Theatre introduced audiences to playwright Rolin Jones and his harrowing, brainiac comedy, "The Intelligent Design of Jenny Chow." Now, Woolly Mammoth has given us Sarah Ruhl and her sad yet strangely uplifting and funny, play "The Clean House," which will change how you view dusting and Windex forever. Blending elements of magic realism, melodrama and absurdist comedy, Miss Ruhl uses housecleaning as a metaphor for how people alienate themselves from their own lives -- their dust, their dirt. The play gets off to a roaring start with this rant from Lane (Naomi Jacobson), an overtaxed surgeon: "It has been a hard month. My cleaning lady -- from Brazil -- decided that she was depressed one day and stopped cleaning my house. I was like, 'Clean my house.' And she wouldn't." Lane has Matilde (Guenia Lemos) medicated, but still she won't pick up a dust rag. Turns out, Matilde hates to clean. She would rather dream up jokes (which she animatedly relates in Portuguese) in her quest for the ultimate yuk, much like the one her father told to her mother, who died laughing. The perfect joke, she reasons, lies somewhere between an angel and a flatulence episode. On the other hand, Lane's sister Virginia (Sarah Marshall), loves to clean. A suburban nutcase whose beige separates and practical bobbed hair belie a woman who has slowly, quietly become unwound, Virginia takes a romantic view of dusting and mopping, seeing order as a way to get her "self" back. Virginia also finds spiritual meaning in cleaning. To her, housecleaning is not a chore people should palm off on someone else when their economic status rises to a certain level. It is a ritual, a way you take care of yourself and others, a way to make your space sacred and immaculate. Virginia starts secretly cleaning her sister's house, and she and Matilde forge a chatty friendship, filling their days with laughter, jokes and expertly folded laundry. The tidy arrangement falls apart, however, when Lane's husband Charles (Mitchell Hebert) leaves her for one of his patients, the magical and glowing Ana (Franca Barchiesi). Up to this point, "A Clean House" is elegantly neutral, with the actors wearing understated beige, white and black outfits by costume designer Anne Kennedy and Narelle Sissons' set, an expensive expanse of white with tasteful touches of silver. A towering wall of sheer white curtains flanks the back of the set, suggesting wealth but also the generic coldness of hospital curtains. Ana arrives as a welcome burst of brightness, in clothes the color of the sea and blooming flowers. She also brings in assorted messes, both physical and emotional. Lane's spare living room starts becoming littered with the detritus of a real, marvelously disheveled life -- discarded apples the color of jewels, mismatched chairs, a fighting fish in a bowl. "The Clean House" traffics in cliches, especially the one where ethnic people show uptight WASPs how to live, laugh, love. This sentimental notion may stick briefly in your craw, but Miss Ruhl circumvents the schmaltz with writing that is crisp, strident and bitingly funny. Her shifts between the comic and dramatic are clean, never veering into pathos. She keeps the play on course with straightforward dialogue, which the characters speak with bracing directness. Director Rebecca Bayla Taichman takes the play's squared-off neatness to heart, with a staging that is simple yet capable of veering off into flights of fancy where needed. The actors are similarly dedicated to the play's pristine mandates, their roles honed to the point where they seem profoundly intimate with what makes their characters tick. Miss Marshall is nothing short of amazing as the muted oddball Virginia, whose constricted body and facial tics are short stories in themselves. As her successful sister, Miss Jacobson displays preening self-confidence that is a risky choice because it initially makes her so unlikable, but then she lets us in on the uncertainties and pain of someone seemingly so perfect. Both actresses also have the shorthand of true sisters down pat. Miss Barchiesi is a tribute to the seductive power of someone well over the age of 21 who effortlessly enchants everyone she meets, and Miss Lemos exudes the frisky, rubbery demeanor of a born comedian. In the difficult task of being the only male on a stage full of vibrant women, Mr. Hebert more than holds his own, portraying Charles as a man clumsily, passionately reborn through his time with Ana. In "The Clean House," Ana and Matilde bring everyone back to life -- to dirt and dirty jokes, to laughter that is both life-giving and taking. In the process, both Lane and Virginia break out of the hermetic shells they've built for themselves over the years. By getting a little muddy, they come clean, so to speak. |

| CURTAIN UP |

| "The Clean House" |

| Rich See |

Having settled into a spic 'n span new space, Woolly Mammoth is offering a wonderfully funny, quirky and life-affirming production of Sarah Ruhl's The Clean House as their final show of the 2005 season. Naomi Jacobson's and Sarah Marshall's battling siblings offer up a rare treat of women in the comedic throes of mid-life crises. Lane (Jacobson) has hired a Brazilian housekeeper because, as she puts it, "I'm sorry, but I didn't go to medical school to clean my own house." Unfortunately her housekeeper Matilde seemingly suffers from depression. After putting Matilde on medication, the good doctor thinks all is well. Except that it's not Matilde the housekeeper who is cleaning, but Lane's sister Virginia who is actually dusting, mopping and wiping up the bathroom tiles. Virginia (Marshall) is a lonely woman in a benign marriage who is imploding from a life of fear-induced safe living. Meanwhile, Lane is a woman so tightly wound, she makes granite counter tops look cozy. And Matilde (pronounced "Machu-gee"), simply wants to create the perfect joke as a way to transcend her own personal grief. Recently transplanted from her homeland, Matilde is recovering from the duel deaths of both her parents. Her mother died while laughing (choked to death on a bit of spittle) from a joke her father had created for their wedding anniversary. Stricken with grief, her father then committed suicide by shooting himself in the head. So Matilde has come to the United States to leave the unhappy memories behind her. Unfortunately, she is in the wrong career, because she is a housekeeper with no interest in cleaning anyone's house, not even her own. Virginia, however senses that Matilde is as lonely as she and makes an offer to do the cleaning, so long as Matilde does not inform Lane of the duo's agreement. Virginia is a woman who self-describes by announcing "If I were to die, at any moment during the day, no one would have to clean my kitchen." As she tells Matilde, by 3:15 PM her house is spotless with every item neatly tucked in its place. And then she... has nothing to occupy her mind. Lane and Virginia are sisters who get along like a mongoose and cobra. Each eying the other warily, their sibling rivalry has never ebbed. Lane needs to constantly feel superior, while Virginia seethes inside from her own sense of inferiority. Lane's surgeon husband Charles has recently begun to spend more and more time at the hospital and Virginia neatly surmises that if you don't clean your own house, you won't really know your own life. And if you don't do your own laundry, you won't know your husband is having an affair... Ruhl's play takes a white American, upper class longing for purchased order and tidiness and juxtapositions it against a Latin American love of free flowing ambiguity. The result is writing that is somewhat poetic and at the same time, cleanly almost sparingly written. The characterizations are witty and there are moments of wonderful comedic insight on culture, love and sibling relationships. The Clean House is not without its rough spots. The wrap up of the play is somewhat forced. The arrival of Charles could actually be snipped out and reworked to have a more congruous sense of forgiveness. In fact, it actually undoes the wonderfully touching "wash women at the community fountain coming together to share their lives" moment which occurs just prior to his reentry. And the timing of the play needs to be extended. The idea of tightly wound Lane coming to terms with her philandering husband and failed marriage makes no sense in what appears to be a six week (or less) time period. Director Rebecca Bayla Taichman has an innate sense of the Zen aspects of House, while also understanding the screwball comedy touches which flourish between the characters. The timing of the lines and the attitudes are wonderful. The pace never lags. Much of the joy of the performances is contained in the actors' slow building expressions and escalating mannerisms. Like a good joke or a coming storm that will clear away the humidity, the piece builds upon itself in an enveloping crescendo and then gently subsides away. Narelle Sissons' multi-use set design is a metaphysical, Zen-like space with the antiseptic aura of an operating room. It's lovely, but ultimately the kind of room where everyone is afraid to sit. A space of white, beige and tan, that it's cosmopolitan chic is immediately evident. Minimalist decor rules and nothing personal is contained in this antibacterialized "living" room, where ultimately no one is really living but simply existing. A 25-foot closet door holds a plethora of cleaning supplies which the carpet and rectangular design seem to lead directly to, as if they are pathway to a temple entryway and an oracle-like religion of cleanliness. A lone plant -- the one bit of color in the room that is perhaps symbolizing new growth -- stands sentry to the closet door. The use of huge windows and long flowing white drapes meld fantasy and reality and add to the spiritual aspect of the comedy, which ultimately is about barren people coming alive again. Colin K. Bills lighting uses a variety of white light to set the tone. The opera-like overhead titles add to the dramatic satire aspect. Anne Kennedy's costumes evoke an aura for each character. Lane is dressed solely in white, Virginia in beige, Matilde in black, and Charles in muted green. Ana, the dying woman, is dressed in floral prints since, living in the moment, she is truly the most alive of the group. Michael Kraskin's sound design, interspersed with Martin Desjardins' original music, creates a wonderful sense of place. Gerard Kunkel's guitar playing with Michael Sommers' lyrics and Michelle Desjardins vocals bring the Latin flavor to the surface. The ensemble cast is terrific. Guenia Lemos' Matilde is infectious as the woman bringing life via humor into what amounts to a tomb-like space. Ms. Lemos' line delivery and expressions belie her drab, black outfit and add an orphan child aspect to her character. Mitchell Hébert's Charles is a sort of Ivy league everyman. You see him at a cocktail party, listen to him speak competently on many subjects and then forget about him. Perhaps not the idea of dashing that you expect from Lane and Virginia's poetic descriptions, but when you realize that this is their idea of dashing, then he seems correct for the role. And Mr. Hébert adds a winsomeness to Charles that is engaging. As Ana, Franca Barchiesi crafts an independent woman who loves life while acknowledging the reality of dying. As the most alive member of the cast, hers is interestingly the least humorous character. The others are funny in their dysfunction. As Ana, Ms. Barchiesi provides us a woman who has become in tune with herself by simply accepting her flaws and the realities of life. Thus she becomes the straight man in this farcical romp. It's to Ms. Barchiesi's credit that she finds the subtle humor and more tender emotions that make us find Ana a likeable character. Looking as if they are enjoying every minute, Naomi Jacobson and Sarah Marshall as the battling Lane and Virginia, provide moments of physical humor that conjure up the screwball comedies of Hollywood. Whether it's Ms. Marshall having a breakdown and trashing Lane's living room or Ms. Jacobsen's flinging herself on a vacuum cleaner, the two hit upon a variety of comedic levels. While Lane hides her insecurities, Virginia wears her's like a name badge on her sleeve. In characteristic fashion, Ms. Marshall's quirky Virginia is a woman living life on the edge of sanity. Mistrustful of any passionate emotion she lives in fear of coming undone, even though she is inwardly imploding under the stress of not expressing herself. Her maniacal facial expressions, decisive pauses and unique way of phrasing a line make Ms. Marshall's performance thoroughly enjoyable and wonderfully idiosyncratic. Thus when she says "My sister has given up the privilege of cleaning her own house." and then "I love dust." you are assured of an interesting experience. Meanwhile Ms. Jacobson's Lane is a like a rubber band about to be shot across the room. Uncomfortable in her own skin, she is almost clinically sterile. Her two second pause reactions to other's lines and constant look of pained confusion add depth to statements like "I don't always understand the arts." The irony of her being a doctor who seems completely uncomfortable around people is evident in every aspect of her performance. Yet her child-like crouching on the floor or couch show an inner humanity that is completely devoid in the physical appearance. You understand how Charles could leave her, while at the same time you feel for her because she has obviously pushed aside a warmer, inner aspect of her psyche in an attempt to win the race to be at the top and hide her insecurities. Set in "Metaphysical Connecticut" the The Clean House is a witty look at the spirituality of everyday life and becoming aware of the clutter that is building up in your soul like the dust in your living room. It's definitely a good time. So tidy up your abode and then head on down to Woolly! |

| WASHINGTONIAN |

| "The Clean House" |

| Chad Lorenz |

Although The Clean House starts with a dirty joke—it’s in Portuguese but the telling of it is still funny—there are some serious truths in this story of a surgeon and her maid who hates to clean. The setup involves Lane, a busy doc whose Brazilian housekeeper has recently refused to do her job. From there the play explores cleaning as a metaphor for how people approach their lives: The accumulation of dust represents time passing, the compulsion to clean reflects a desire for order, and the act of handing over the responsibility of cleaning to someone else means a disconnect from one’s own life. Adding another layer to that metaphor is Matilda, the young maid who’d rather spend her time coming up with the perfect joke than Swiffering the floor. Her pursuit is serious: Her mother died laughing after hearing the most brilliant of jokes from her father. Matilda is equally afraid of and consumed with devising a joke that’s just as funny. But back to our original mess: The worse the house gets, the more agitated Lane becomes. To the rescue comes Lane’s sister, Virginia, whose sole joy in life is cleaning. After Virginia finishes tidying her own house—at 3:12 every day—she secretly sets about the housework at her sister’s, and in the process becomes Matilda’s friend and confidante. Just as Lane uncovers the ploy, another woman enters the picture, an Argentinean patient of her husband’s who is dying of cancer. What develops among the four women is a complex sisterhood. Each woman is distinct and even at odds with the others, but together they complement one another and produce a larger picture of womanhood. Sound dreary? Nonsense—The Clean House is filled with laughs. Naomi Jacobson, who plays Dr. Lane, and Sarah Marshall as her sibling rival, Virginia, are a classic team whose facial expressions and catty barbs—delivered with precise timing—are delicious. In one tense scene, Virginia insists on vacuuming as Lane nears a breakdown, and the doctor attacks the Hoover in an effort to silence it. Guenia Lemos gives Matilda a charm and naivete that create an amusing contrast to the sisters’ acerbic exchanges. However, these three women balance their performances with pathos. Jacobson is convincing in showing how Lane’s hard heart begins to thaw when she relents to giving medical care to the dying woman, though Lane has reason to loathe her. Marshall, who has become one of Washington’s best stage clowns, gives a nuanced performance, confessing Virginia’s own vulnerabilities and drawing out the good in the others. The set, by Narelle Sissons, is Lane’s sleek, modernist living room, all white with Swedish-style furniture. It’s a touch of what audiences have seen recently at Arena (The Goat or, Who Is Sylvia?) and Shakespeare Theatre (Ghosts)—and perhaps a nod to the designer of Woolly’s new theater, Bethesda’s Mark McInturff. Anne Kennedy’s costumes are equally stylish and fitting for each character. Ruhl’s play succeeds as a drama because of its tenderness—it’s touching in a Steel Magnolias way but without the oversentimentality—and because Ruhl has weighty thoughts to share. It also succeeds as a comedy because its strong actors portray the ironies and humor of real life. The play marks a victory for Woolly by showing that the typically bombastic company—whose productions are often laced with profanity, sex, and absurdity—has a softer, more elegant side that’s no less funny and no less powerful. |

| INSIDE NOVA |

| "Clean House" is one vey polished show |

| Gail Choochan |

Everyone likes a clean house. Items are carefully stored away, the carpet is free of debris and the furniture is wiped down for dust. There’s a place for everything and everything is in its place. The characters in Sarah Ruhl’s “The Clean House” know their place, but even the most spotless character is in need of a little polishing. “The Clean House,” the second production staged at Woolly Mammoth’s new Seventh Street home, is enjoyable from start to finish. Set in “metaphysical Connecticut,” the play opens up with a young woman (Guenia Lemos) telling a joke in Portuguese. (The words “A woman tells a joke in Portuguese” light up overhead). The laughs come from in not what she’s saying, but how she’s saying it. Matilde - a cute maid from Brazil - instantly captures the audience’s attention with her animated storytelling and body language. Next in the introductions is her boss Lane (cue the lights), a tough-as-nails doctor. All Lane (Naomi Jacobson) wants is to come home to a clean house and it frustrates her dearly that Matilde has just stopped cleaning. And it’s not like the place is in desperate need of an extreme makeover. Lane’s immaculate, monochromatic living room is taken right from the pages of Metropolitan Home or Elle Decor (furnishings courtesy of neighbors Apartment Zero). White couches, white curtains, white walls, even her suit is white. Lane is an image of power, unlike her meek sister Virginia (Sarah Marshall), a slightly eccentric neatfreak. “I know when there’s dust on the mirror,” she says. Both these women enjoy having a sense of control: Lane over people, Virginia over clutter. Fearing Matilde is ill, Lane sends her to the doctor. But it isn’t a sickness that prevents Matilde from her duties; she just doesn’t like to clean. And it’s obvious when she tries to steamclean husband Charles’ workshirts by hitting them on the rack. Matilde finds a confidant in Virginia and the two work out a deal: Virginia will secretly clean Lane’s house. What Matilde is really good at is telling jokes. She came from a family of funny people and she hopes to come up with the perfect joke. Her quest, though, isn’t without fear. It was a joke, a really good joke, that killed her mother. Her mother died laughing, and her father shot himself soon after. So naturally, Matilde’s afraid that when she finds the perfect joke, it would kill her. Lemos is absolutely refreshing as Matilde. “The perfect joke is between an angel and a fart,” she says in her pursuit. She brings youthful innocence to the play, which often deals with the not-so-great trappings of reality. A finalist for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, “The Clean House” is much more than what goes on in this supposedly picturesque suburban life. Beyond the comedy taking place in the house lies a greater meaning: finding your soul or in Charles’ case, your soulmate. Seriousness weaves through the play at unexpected moments as does laughter. In times of death or sadness, a brief smile may break out. While tending to a mastectomy patient, Charles (Mitchell Hebert) instantly falls in love with her, and Ana - who dislikes doctors - feels an overwhelming connection, too. They decide to move in together. Ana, played exquisitely by Franca Barchiesi, is seemingly a minor character at first, but her passion for life has a great impact on the other characters. While Lane is aghast that Charles would even bring “the other woman” into her house, Matilde is elated. Ana bears a striking resemblance to her mom and Matilde, too, feels an instant connection. Ana’s unexpected arrival serves as a wake-up call. She’s like ray of sunshine pouring through the windows. She exudes it through her personality and her appearance; she comes in wearing a hot-pink dress with little white flowers and perfect makeup. Soon after, Matilde begins to wear a red flower in her hair. The relationships among the characters evolve through the course of the play: friendships are made, marriages are broken and sisterly bonds are strengthened. Company members Jacobson and Marshall each deliver a wonderful and sharp performance, playing characters that seem to be written especially for them. Having seen their previous work, it would be interesting to see their roles reversed. Let Marshall play the conservative and Jacobson the neurotic. Now that would be fun. As Charles, Hebert injects much laughter in his mostly comedic role. While the women tend to a very-weakened Ana, Charles is seen through the glass braving the unforgiving Alaskan weather in search of a medicinal tree for his love. Directed by Rebecca Bayla Taichman, “The Clean House” is a polished piece of work, filled with sparkling characters and a beautiful story about how messy life can be. |

| POTOMAC STAGE NEWS |

| "The Clean House" |

Only Woolly would brag that their new show "overflows with jokes we don't understand," but it is reasonable given the fact that the comedy centers on a cleaning woman who'd rather tell jokes in Portuguese than straighten up. The piece is by Sarah Ruhl, a relatively new voice in theater. This play was one of three finalists for this year's Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Her Passion Play, a cycle, will premiere at Arena Stage in about a month and her take on the Greek myth Eurydice has just been published in a collection of contemporary plays inspired by the Greeks. It's quite a summer for a playwright now in her early thirties. She makes it quite a summer for Potomac Region theater lovers as well. Storyline: A Portuguese-speaking Brazilian housekeeper, who hates to clean, drives her employer nuts. The employer, a successful doctor, has a sister who does like to clean ("if it weren't for dust, I don't know if I'd want to live.") The Brazilian housekeeper and the sister become fast friends while Doc and her husband, also a successful doctor, are at work. Things come totally unglued when husband/doctor falls in love with a patient and decides to leave his wife. This is a play about the power of laughter, not the dangers of dirt. It begins with a superb short vignette in which Guenia Lemos, as the Brazilian girl paid to clean but who is much more interested in "finding the perfect joke," tells the audience a joke in Portuguese, while the projected surtitle simply says "Matilde Tries To Tell The Perfect Joke." The scene could bomb if it weren't for the infectious spirit shining in Lemos' eyes. She's so compelling, and her faith in the humor of her story so apparent, that the audience laughs at the punch line without the slightest idea of what it is all about. What it is about is the magic of theater and that short scene uncaps wonders. Naomi Jacobsen carries the magic a step further by creating a portrait of the home-owning doctor that, while serving the needs of the story with her cleanliness thing ("I didn't go to medical school to clean my own house!") never completely crosses the line to become a total shrew. When she discovers Sarah Marshall (as her sister) has been cleaning, she is revolted by the thought that family members might be pawing through her underwear. Marshall brings her trademark ability to make quirky completely believable - just watch her work a folding board! The relationship between husband/doctor (Mitchell Hébert) and his life-loving patient (Franca Barchiesi) seems like a sub-plot to begin with, but blossoms into a compelling part of the full ensemble story in the second act. Set designer Narelle Sissons, who has extensive credits around the country, and who contributed the slightly too-neat set for The Theatre of the First Amendment's Open the Door, Virginia! earlier this year, comes up with a stunning set for Woolly's new home on D Street. A back wall of a ceiling to floor sheer curtain not only establishes this up-scale living room as the antiseptic, colorless abode of wealthy but busy professionals, but it allows glimpses through the windows behind to a more colorful, if messy, world. Colin Bills' lighting emphasizes the distinction between the two locales and Anne Kennedy's costumes complete the look with sparkling white for Jacobson, beige for Marshall, black for Lemos but bright pinks and turquoise for Barchiesi and Hébert. |

| METRO WEEKLY |

| A Perfect Mess: Absurd, surreal and touching, 'The Clean House' is an unexpected regal play brushed with a sense of magic |

| Jolene Munch |

For the record, it really doesn't matter if you don't speak Portuguese -- you'll still understand the gist of Matilde's jokes in The Clean House, an exotically domestic comedy filled with unfamiliar comforts of another world. Cosmically set in ''a metaphysical Connecticut,'' The Clean House is home to Lane and Charles, two successful (read: busy), married doctors living in a house as sterile as the hospitals in which they work. Their antiseptic living room (as designed by Narelle Sissons) is a vision of slate blue and white, indicating pure, unspoiled hygiene and unruffled discipline in décor. With all of these polished lives and neat, gleaming furniture to look after, it's too bad their live-in maid doesn't like to clean. Matilde recently moved to the States from Brazil after both of her parents died. ''My parents were the funniest people in Brazil,'' she intimates. No, really. Her mother died from laughing at one of her father's jokes. Then her father committed suicide. After that, there was no one left to laugh at Matilde's jokes, so off she flew to clean houses in America while trying to think of the perfect joke. Then there's Lane's sister, Virginia, a housewife obsessed with cleaning as a means of emotional therapy. ''If you do not clean," she says, "how do you know if you've made any progress in life?'' The solution is simple: Virginia will secretly clean her sister's abode while Matilde thinks of her joke. It's a relatively perfect arrangement until an ''impossibly charismatic'' stranger waltzes in and knocks each woman off of her own tightrope. Sarah Ruhl doesn't know it, but she's written a classic Woolly Mammoth play, brimming with quirky characters, lively dialogue, and deft insight. No one else could produce such a sparkling comedy and lace it with heart-pricking drama the way Woolly has. Sometimes absurd, sometimes surreal, but always touching, The Clean House is a rich and unexpectedly regal play brushed with a marvelous sense of magic. It's also a recent Pulitzer Prize finalist, and Ruhl's script is a cerebral playground of memories and indecipherable Portuguese jokes that bubble up from a barely-tapped spring of humor and poetry. There are stage directions -- and other internal notes -- projected in surtitles above the stage, such as ''Virginia has a deep impulse to order the universe'' or ''Lane makes a house call to her husband's soul mate.'' These small asides serve up a perfect irony of realism scattered throughout The Clean House, reminding us that reality and dreams of reality sometimes intertwine to fantastic results. With spotless direction from Rebecca Bayla Taichman and a perfectly appointed cast plucked from the heavens, 'The Clean House' features a round of honest, intelligent performances from an ensemble of five first-rate actors. Guenia Lemos is a charming ''Machilgee,'' who informs us that ''a perfect joke is somewhere between an angel and a fart,'' while Naomi Jacobson gives an exceptionally taut interpretation of Lane. Whether scorning her sister or attacking a vacuum cleaner, Jacobson is a frozen solid ice cube that ends up melting under the warmth of compassion and humanity from Franca Barchiesi's rapturous Ana. Barchiesi gives a delicious performance as the Argentinean sprite taken with Mitchell Hébert's Charles, a childlike surgeon who has at last found his apple-picking bashert. But it is Sarah Marshall's wide-eyed, high-strung Virginia who packs the most punch with her relentless neuroses. Marshall is a sheer delight to watch unravel as she fondles her brother-in-law's briefs or makes an ''operatic mess'' of things in her sister's house. All five don smart, immaculate costumes by Anne Kennedy, and Sissons' whimsical set is lit with startling precision by Colin K. Bills. A brilliant examination of loyalty and the individual entitlement to happiness, Ruhl's seriocomedy is a perfectly stunning and poetic reminder that life isn't always beautifully orchestrated -- it's a messy, perpendicular series of losses and gains. And after visiting The Clean House, you'll imagine the possibility that perhaps life somehow finds a way of making everything that's dirty clean again. |

| THE EXAMINER WASHINGTON |

| "House" keeping: Woolly Mammoth goes to the "clean" extreme |

| Denise Pringle |

The Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company is hosting its second play in its new home. And true to the company's "nothing in moderation, so let's find an extreme" sort of spirit, "The Clean House" — with its pristine living room set design — is visually as far removed from the suspended wrecked car and doomsday theme of their inaugural offering "Big Death and Little Death" as it could possibly be. But a visit to the Woolly Mammoth always includes radical issues interwoven with the ordinary, and a study of contrasts is their norm. How else could you visit "The Clean House" and find a home in the care of a maid who has realized that she really doesn't like to clean? Playwright Sarah Ruhl has written Matilde (striking Brazilian actress Guenia Lemos) not as some sort of anthropomorphic oxymoron come to life, but simply as a young woman on the important quest of writing a perfect joke who has become trapped in a maid's existence. Lemos infuses Matilde with charisma, and you can't help but be charmed when she suggests that one simply look at the ceiling if they find the dirty floor too difficult a sight to bear. On the other hand, Naomi Jacobson (as her disgruntled employer, Lane) has a much more pragmatic view of the dilemma. She is too busy and too well-educated to clean her own house, so there must be some sort of medication to make the maid resume her duties. A messy cleanup In an ordinary theater, this is probably enough conflict to keep a play going, but remember you're at Woolly—let's really create turmoil here. Enter Lane's sister, Virginia (a rubbery-faced Sarah Marshall), who lives to dust. Let's team her with Matilde, get the house cleaned and make Lane happy, OK? Not so fast — Lane feels violated by these conspirators. And we're just warming up. Lane's husband, another doctor, has fallen in love with his Brazilian patient with terminal cancer. Now there's our plot—just try to clean up that mess! Director Rebecca Bayla Taichman accents the fun in this dysfunctional family unit's day-to-day existence. How long can Lane really stay angry with a sister whose epitaph may one day read, "When I died, you didn't have to clean my kitchen," and who thinks that dust is an integral element in tracing progress? And how quickly can she forgive her husband and learn to care for his new love? And why will she fight for the services of a maid who doesn't clean? You'll find yourself laughing at these implausible situations even when you're not sure why they are funny. Interior decorating At first glance designer Narelfe Sissons has created an impeccably clean and tasteful living room for the couple of doctors; its hidden assets add to the physical humor later. The broom closet is a dustaholic's-dream and the sheer curtains let you glimpse into other worlds—sandy beaches and snowy wastelands. No doubt she enjoyed the artistic stretch that the spacious new Woolly theater can accommodate. An interview with the playwright revealed that the concept for this play was a conversation overheard at a cocktail party. If you at first doubt that this idea of cleanliness could evolve into a couple of hours of theater, think again. Why do many people feel the need to clean not only before guests arrive, but before their own maid come in to clean? Ever feel the need to clean before you go away for a weekend? Can you concentrate on a difficult project before tidying up your own workspace? A rage for order is a pretty basic need, after all, and the collective performances of this gifted cast will have you in the palms of their rubber-gloved hands. |

| WASHINGTON THEATRE REVIEW |

| "The Clean House" |

| Fiona Zubin |

At its best, The Clean House is nearly indescribable, an eddy of wit, rage, death, dirt, and white furniture. At its worst, the play brings to mind an irritatingly "arty" foreign film, one of those black and white movies that uses slow motion like it's going out of style and always manages to insert blissful peasants reveling in sensual tasks. Fortunately, that is the only remotely disparaging thing that can be said about Woolly Mammoth's latest production, a sharply funny, ultimately moving work that is able to lovingly mock its own pretensions. Tightly-wound doctor Lane (Naomi Jacobson) is awfully stressed out for someone with such a perfect life—successful marriage, successful career, and a terrifyingly all white house (wittily designed by Nerelle Sissons.) Her Brazilian maid, Matilde (Guenia Lemos), is preoccupied with the study of untranslatable humor and the search for the perfect joke, which is "somewhere between an angel and a fart." Despite Matilde's truancy, Lemos is so unbelievably charming that she manages to garner laughs even when speaking to the audience in Portugese. Enter Virginia (Sarah Marshall), Lane's younger sister. Virginia is a bug-eyed housewife with nothing to do and a slightly scary dirt fixation. Marshall's performance is unendingly funny, even as the poignancy ofVirginia's soul-destroying boredom is made clear. And then there is Ana, an Argentinian senior citizen with a demeanor somewhat reminiscent of a young Sophia Loren. She interrupts the white and beige of the rest of the play, with splashier costumes and more melodramatic problems than the rest of the cast. Mitchell Hebert, as the solitary male in the cast, manages to be hilarious while at the same time making his character seem like an entirely unfunny man. He gamely offers support, but this is a play for women, so though he gets his share of moments, he cannot be included in the emotional connection that flourishes between the four actresses who give the play its heart. This is a play about women and their relationship to their homes and their own dirt: Lane has no time to clean, Matilde has no inclination.Virginia can't do anything else, and Ana sees cleaning as a form of masculine oppression. Playwright Sarah Ruhl explores how the state of our homes affects and is affected by our states of mind, how cleaning figures into out perceptions of femininity, and the differences between cleaning your own house and cleaning someone else's. Ruhl has concocted a play that considers these issues in a personal, rather than political light, and the most surprising thing is that such an intelligent and thoughtful piece can be so screamingly funny at the same time. |

| WASHINGTON CITY PAPER |

| "The Clean House" |

| Trey Graham |

“Love,” says the pretty Brazilian in the mourning blacks, "isn't clean....It's dirty, like a good joke." And there's The Clean House in small—all its sweet, generous philosophy summed up in an uncluttered little passage from playwright Sara Ruhl, a buzzed-about West Coaster making her Washington debut at Woolly Mammoth. There's whimsy in her simile, and a slight, mischievous smile, and a frank assertion that the simplicities we chase aren't nearly as good for us as we imagine they will be. It's a script that could go sour or saccharine with equal ease—it’s unlikely characters could seem like a capricious author's stick figures, its insistence on their redemption could come off as hopelessly naive, and its flirtations with the tropical woo-woo of magic realism could easily tip over into twee. But in this, the second production in its sleek new downtown digs, Woolly makes a case for the play as something pretty special—and for Ruhl as a writer worth listening to carefully. The white-on-whiter-than living room in which we've gathered exists in what Ruhl calls "a metaphysical Connecticut," in the painfully perfect home of a beautifully put-together doctor who's having a bit of a bad month. Her name is Lane, and the aforementioned Brazilian, her live-in housekeeper Matilde, is too depressed to clean, and well, "We took her to the hospital and I had her medicated," says Lane, played by a sublime Naomi Jacobson as a woman very much on the verge but so far no luck. "In the meantime," Lane says as if it’s the least conceivable development imaginable, "I've been cleaning my house!" Cue her sister, Virginia (Sarah Marshall, getting her reliably inventive quirk on), who's got a bit of a cleaning thing. "If there were no dust to clean then there would be so much leisure time and so much thinking time and I would have to do something besides thinking," she tells us all in one confessional rush, "and that thing might be to slit my wrists." Clearly, she and Matilde are made for each other—and sure enough, The Clean House's story involves a secret deal wherein Virginia cleans for her sister's cleaning lady while Matilde pursues her dreamy, distracted quest for the perfect joke—until the fatal day upon which Lane's husband leaves her for a patient and a near-hysterical Lane discovers the tidy little arrangement that's been keeping everybody sane. The almost too-cutesy setup is all but beside the point: Ruhl finds poignancies, it's true, in the whys of Virginia's obsession and the wherefores of Matilde's wistfulness, but the play's real arc is the one Lane travels in Act 2, after Mitchell Hebert's Charles brings his enchanting new lady, Ana, home for an introduction. "I want to do things right from the beginning," he says, looking guileless and puppyish and explaining that Jewish law requires a man to leave his wife if he discovers his bashert, or soul mate. Jacobson's Lane responds with what can only be described as a series of escalating but rigidly controlled boggles, plus an inevitable observation—"You're not Jewish"— but the play will insist that, yes, peace can be made, that forgiveness can be found, that charity, when one of this motley assembly suddenly needs the others, can put down roots even in a house scoured thoroughly clean, of anything so messily complicated. Woolly's beautifully contained production keeps the sentimentalism in check, and director Rebecca Bayla Taichman treads gently around the places where Ruhl's sense of the fantastical makes itself felt. Apples, when Charles and his paramour take Matilde picking, rain down in Lane's sterile living room like little gifts, bringing a sense of something organic into her chill surroundings for the first time all night; at various points, when Matilde remembers the parents whose death is behind both her sadness and her search for the perfect joke, a laughing couple drifts by beyond the vast wall of windows; when Lane imagines Charles with Ana, they appear in her living room, where Matilde can somehow see them. The cast, crucially, never for a moment seems conscious of affectation. Franca Barchiesi, lithe and physically lyrical as a dancer, makes Ana every inch the warm, sensual salvation Ruhl imagines in her script. There is both mischief and melancholy in the eyes of Guenia Lemos' quietly impish Matilde, and if Marshall maybe hasn't discovered the gravity of Virginia's nervous condition, she's certainly discovered the humor in it. Hebert makes Charles the bad guy without making him in the least bit a bad guy, which is just what Ruhl is after, and Jacobson is, I can't say enough, delicious. Together, they and their Woolly colleagues have made the impending Arena Stage premiere of Ruhl's sprawling Passion Play, a Cycle a more tempting prospect than that California production had hinted at; if, come September, Molly Smith & Co. can meet this gifted writer with as much sense and sensitivity as their colleagues across town have, it could be a season-opener worth shouting about. |

| THE DOWNTOWNER |

| "The Clean House" |

| Gary Tischler |

Everybody's heard this line: “I laughed so hard I cried.” Or, pumping up a joke: "This one will kill ya!" Both things happen in'"The Clean House," a remarkable play by the very gifted, very wise playwright Sarah Ruhl, and they .happen during the course of a production at the Woolly Mammoth Theater's new digs. As we all know, there is no crying at Woolly, which is in a league of its own. But I bet you'd come close somewhere in this play, maybe when you least expect it. This is one of Ruhl's great gifts. She—and her characters—surprise you, almost at every turn, with every utterance. Also, director Rebecca Bayla Taichman and an impeccable cast serve the play's hot-wired emotional turns as if they were plugged in directly. Afterward, you think her choices were just so. And you remember, among other things, how hard you laughed, how funny the show is. After all, it's only about marital sterility, adultery, cleaning house, jokes that kill, death and cancer and lots of other hilarious things. So you think you've got a case of really dark humor here, right? Well, no. The humor is funny, but it's sunny. In a strange way, it's affirming and releasing. First off, we have a tidy tittle play about the edgy, really wound tight Lane, a successful doctor who has a Brazilian cleaning girl named Matilde, who hates to clean. Actually, she couldn't be bothered, because she's too busy trying to think up the perfect joke, in Portugese, because her parents were happy, funny people. "My father spent a year thinking up the perfect joke and when he told it to my mother, she died," Matilde explains to the audience. Lane goes so far as to send Matile, played with beguiling and charismatic naturalness by Woolly newcomer Guenia Lemos, to a shrink, but things change when Lane's sister Virginia shows up. Virginia loves to clean, it gives meaning and order to her life, it shows "you're making progress." An unhappy housewife, she befriends Matilda and together they keep order in Lane's world. Except that Lane discovers the ruse, fires Matilda about the time she finds out that her eminent surgeon husband is an affair with a patient, an older woman upon whom he's performed a mastectomy. End of act one. This doesn't go where you think it will go, of course. Because the woman is Ana, played with uncommon strength by Franca Barchiesi, and because Ana is something of a good witch, she can cast a spell and rearrange whole pieces of your heart. Naturally, she bonds with Matilde, but she also eventually thaws out Lane, who until then has lived with such rigid certainty that it's hard to imagine her without that straight-lined white pants suit. Where this goes-—that next turn—is redemptive, it's as if everybody, including the dying Ana, is set free through jokes, forgiveness, through almost unbearable honesty. Sarah Marshall as the searching Virginia and Naomi Jacobsen as the tight-lipped Lane give almost textbook lessons on how to act by reacting. Earttishaking things are happening in their lives and it plays out on their faces, in how they stand up and sit, where their eyebrows go, how their heads turn, not so much in what they say. Marshall's acting is always malleable, and here she has a character and a writer who's as unpredictable as she is. Jacobsen's Lane is all icy precision, she wins the compulsory part of life all the time, until the ice melts under her. Only the part of Charles, the husband, seems a little underwritten. He's a catalyst, but he's also heroic and Mitchell Hebert does what he can with the man, achieving the result that, having done the unforgiveable, he insists on being forgiven and we forgive him. In the writing, Ruhl is clear eyed about everything, happily balancing on the high wires that separate sentiment from sentimentality, really witty, funny humor from off-putting crudeness, magic from ordinary nonsense. In this production, everyone .is in sync to make real magic out of magical realism. Narelle Sissons's stunning white, shades-of-grey, immaculate set, which includes one of those all-white canvas paintings that might be in Diane Sawyer's living room, is just waiting to be spilled on in a chaotic way. Anne Kennedy's costumes define the characters, how they're imprisoned and set free. |